As I pull up to the Carova Beach access point, I’m a little nervous. Signs warn only four-wheel drive vehicles are permitted and to let air out of the tires. I’ve heard lots about the popular spot in the Outer Banks — known for its wild horse population and remote location — but this is my first visit. Plus, I’m using Mark’s truck.

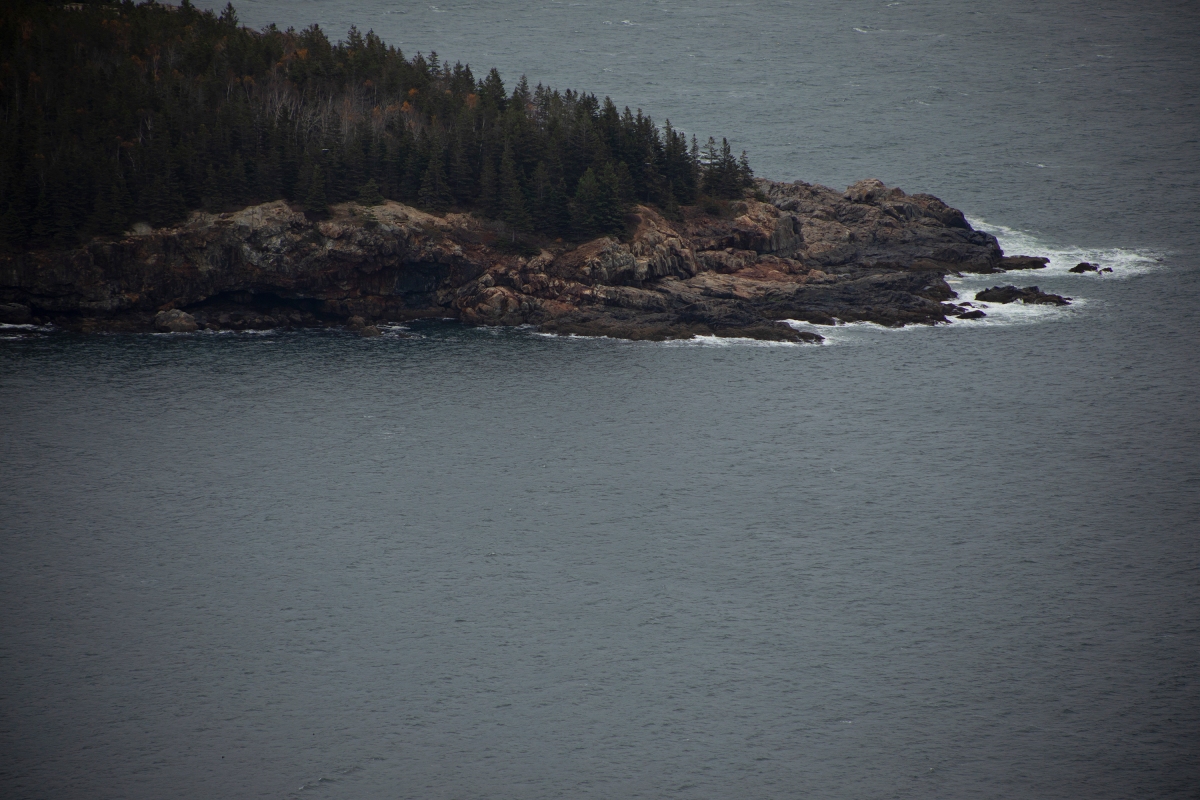

There’s some sliding of the vehicle in the deep, soft tracks, but after a few minutes I get the hang of things and can take in the view. Fresh from heavy storms, the Atlantic waves crash ashore in droves. Sea birds swoop and dive for their morning meals. About 20 minutes and one slightly precarious detour later I spot what I’ve come here for.

I park the truck, hop out, and take in the sight of a 26-foot female minke whale. In the whale world, she’s not a giant but to someone who has never seen a whale in person, she’s massive. It’s too bad my first encounter is under these circumstances.

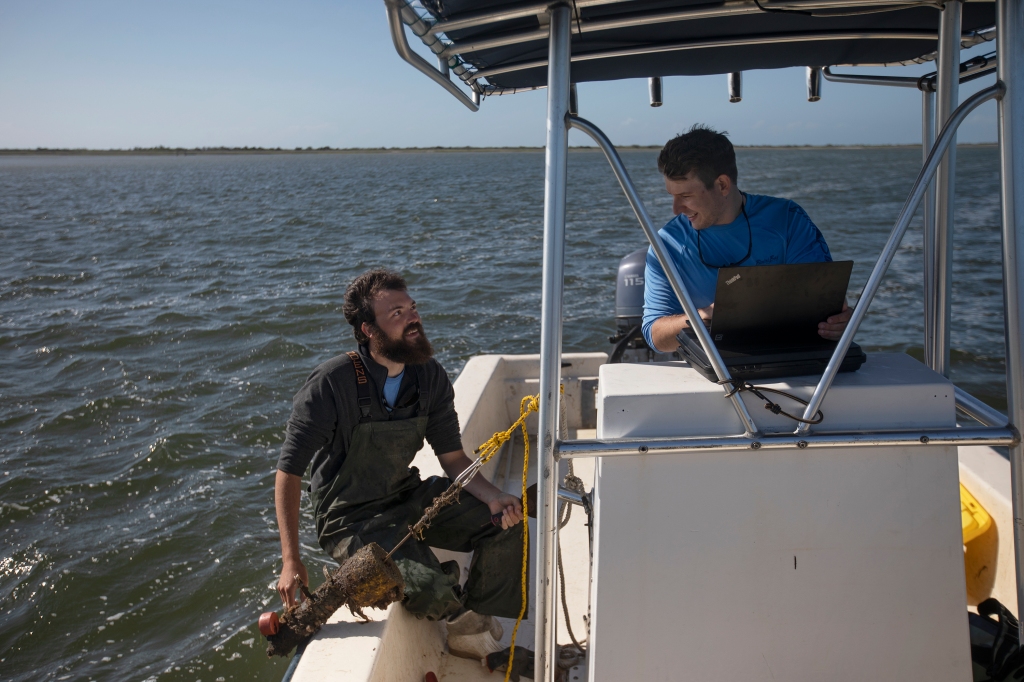

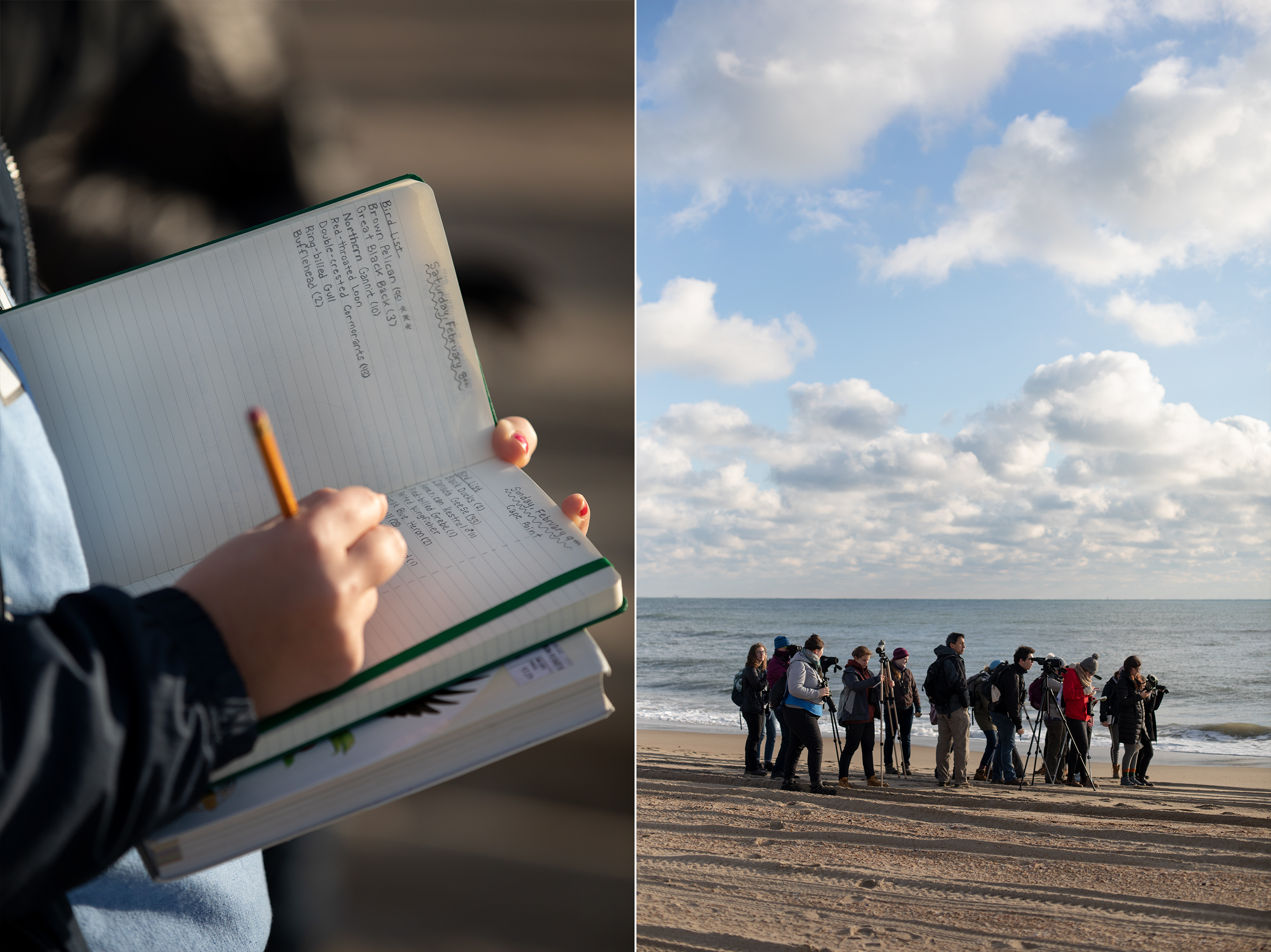

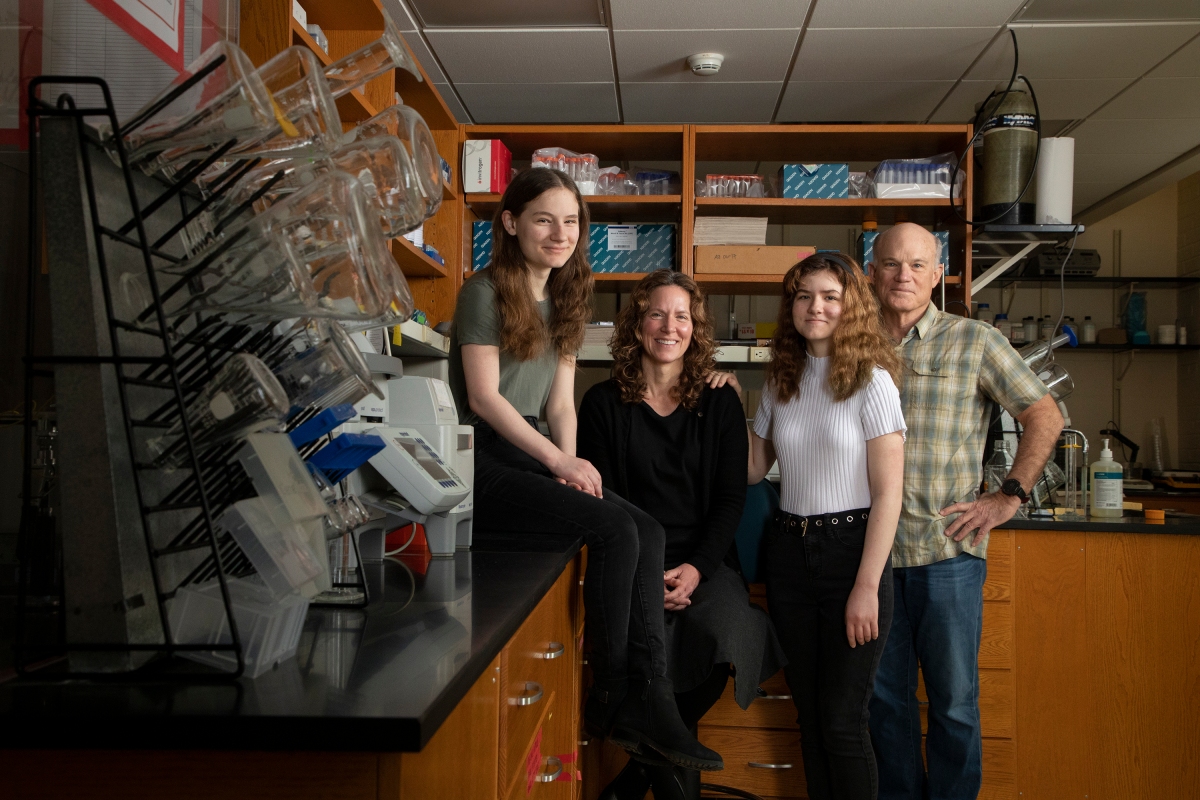

It’s not long before the others arrive — researchers from NC State University, the NC Division of Marine Fisheries, UNC Wilmington, the North Carolina Aquarium, Jennette’s Pier, and volunteers are here to perform a necropsy.

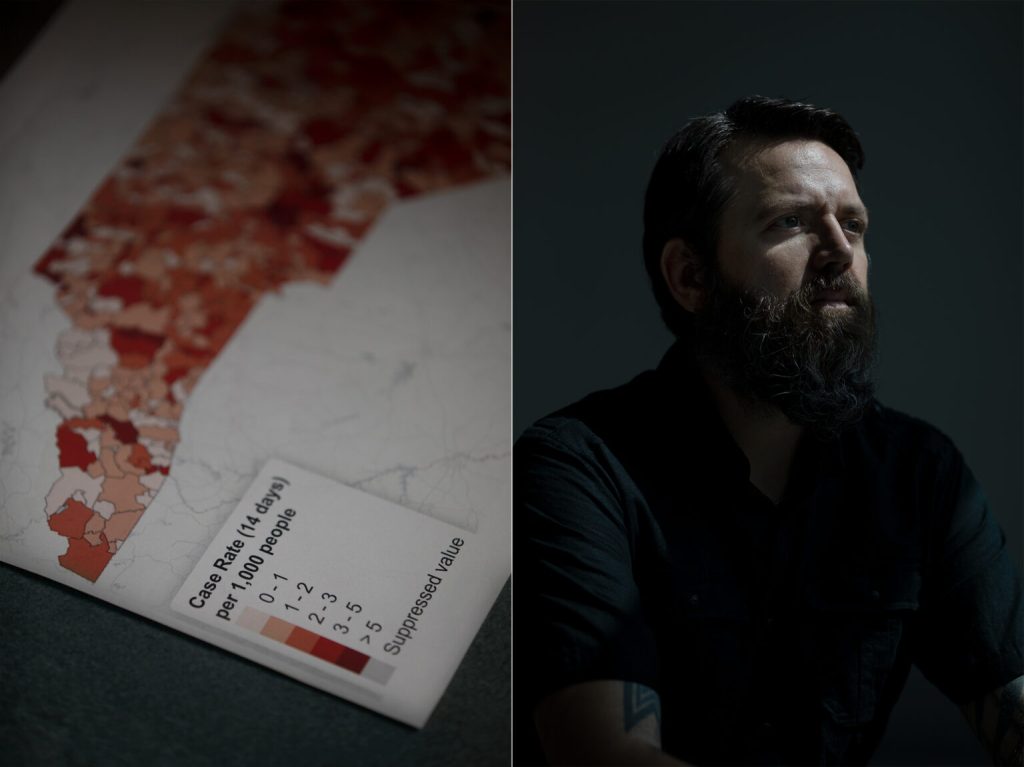

The whale was the third found in the area in just as many days. Earlier that week a humpback whale washed ashore in Virginia Beach, followed by another at False Cape State Park. The same day this necropsy was performed, a pregnant dwarf sperm whale and juvenile male dwarf sperm whale washed ashore in nearby Nags Head. The following day, a bottlenose dolphin was also found at Nags Head and a common dolphin was found at Southern Shores.

Since 2017, elevated minke whale mortalities have occurred along the Atlantic coast from Maine through South Carolina, totaling 164 as of 2023. Minke whales aren’t alone in this predicament — according to NOAA, unusual mortality events are also active for the Atlantic Florida manatee, gray whale, North Atlantic right whale, and humpback whale. Causes range from vessel strikes, fishing entanglements, disease, and changes in ecological factors.

A hot debate right now is the effect of offshore wind on marine life, but these claims are not supported by research. Additionally, far right groups are proponents of this in their efforts to block green energy projects.

No evidence of human interaction was found on this whale, but she had obvious signs of a bacterial infection throughout her body. At this point though, more analysis is needed before a conclusion can be made.

While it’s unusual to find this many strandings so close together in space and time, Craig Harms, a researcher from the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine and Center for Marine Sciences and Technology, says that may just be an unfortunate statistical anomaly due to strong currents and waves bringing carcasses ashore that may have otherwise been left at sea.

“Although if this persists,” he adds, “I could change my mind really quick.”

When a whale dies offshore, the carcass eventually sinks and becomes a whale fall — providing a food and habitat for deep sea scavengers, invertebrates, and microbes for years or even decades (check out this amazing video of a whale fall in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary).

When a whale carcass washes ashore, it’s body is used in a different way.

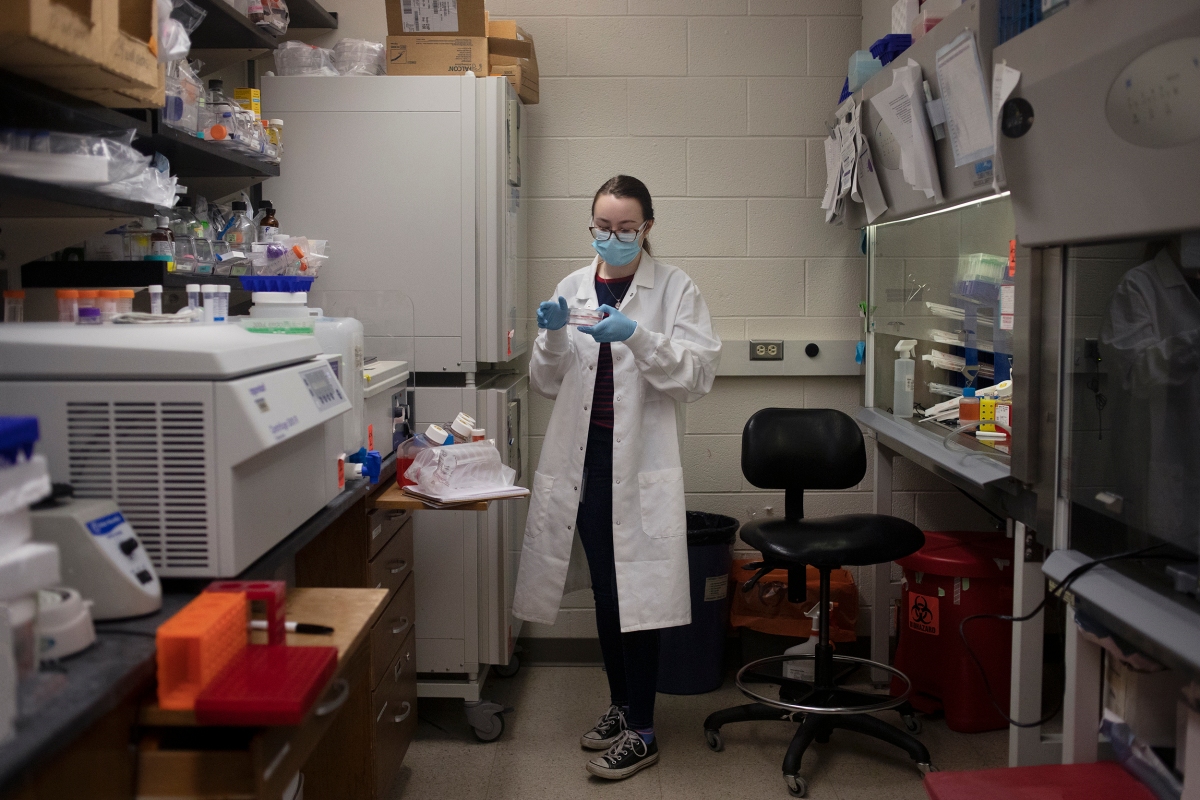

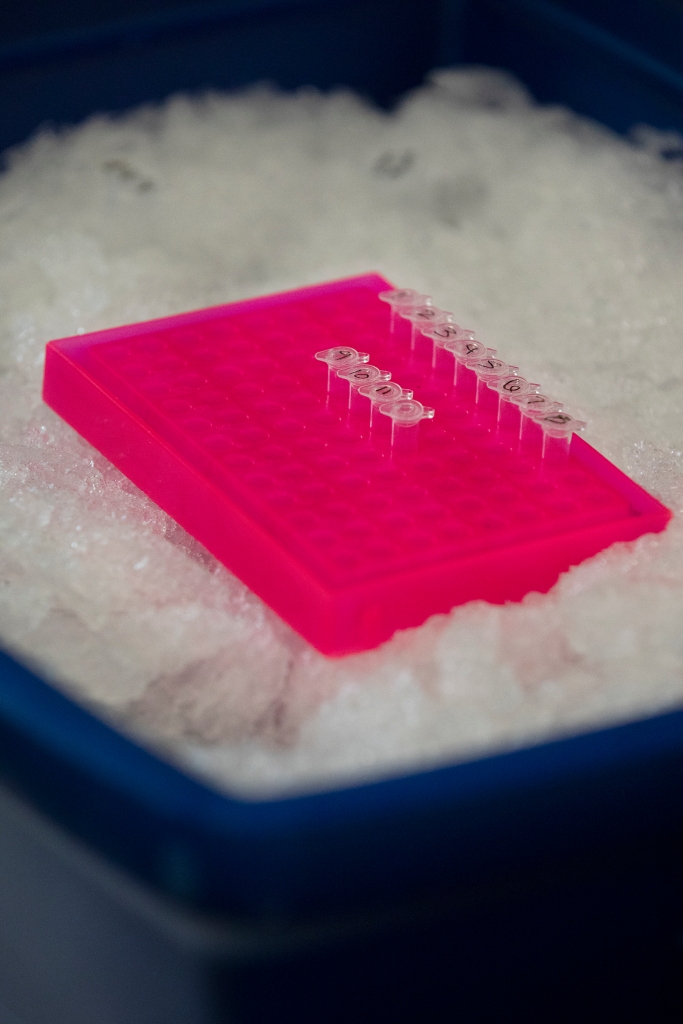

The main purpose of a necropsy is to investigate the cause of death, but samples are also taken to support a myriad of research. Tissue was collected to study diet and dive physiology. Her eyes will be used in research about marine mammal vision. Feces were collected for parasitology analysis. Her dorsal fin was radiographed to map out blood vessels and inform future biological sampling on live animals. Additionally, a variety of samples were gathered to archive for future research or share with collaborators.

While it’s sad to see the death of such an intelligent and impressive animal, it’s beautiful that — like in a whale fall — her body will support life for years to come, via science.